アマノイ、ベトナム

ヌイチュア国立公園とユネスコの生物圏保護区に囲まれた、緑豊かなベトナムの海岸線を望む場所に、アマノイは佇んでいます。ここはヴィンヒー湾を見下ろす自然の楽園です。

Photography by Martin Bruno

Words by Akiko Kurematsu

Aman Tokyo, Japan

The last of the cherry blossoms have come and gone throughout Honshu, the main island in Japan. For months, the cherry tree occupies the nation’s conversation – a country that is obsessed with the changing seasons, its symbolic cherry blossoms.

We may have missed the blossoms, but photographer Martin Bruno and I are here in Tokyo in the spring season. I don’t remember the last time I was in Japan in April but still, there are scents and tastes, sounds and feelings that bring me home. I remember the start of the school year, spring uniforms, and picking azaleas. I remember bamboo shoots cooked in rice, and riding on the back of my grandfather’s truck through rows of tea bushes.

My heart beats a bit quicker; in tune with the blooming world around me. At Aman Tokyo, I am walking under a canopy of a small forest at the foot of the hotel, with trees reaching overhead. For three years, this forest grew in the Chiba Prefecture until it was transported to the middle of Otemachi where it thrives today. The forest has grown here for almost a decade, housing its own ecosystem.

I take the elevator and enter the lobby on the thirty third floor. Natural light floods in through floor-to-ceiling windows on the far side of the expansive space, with an ephemeral tree standing in the center. The subtle beauty of this living sculpture is striking, and the scene is set.

I sit and take a moment. Growing up all over the world with roots in Japan has given me a profound appreciation of Japanese culture, a perspective from deep within and from afar. It is a privilege to exist outside of the tight Japanese mold but finding my place here has been a lifelong journey. I’ve learned and earned my Japanese-ness in the form of language and codes of conduct and come to peace with the ways I don’t quite fit in. I’ve had to find comfort in a place where I’m not always comfortable.

A cup of shincha and a fresh hand towel arrives, and I exhale. Brewed from this year’s first harvest, the tea is bright yellow-green and smooth. Sen no Rikyu, famed tea master from the 16th century, used the term ‘ichigo ichie,’ on the incalculable worth of a moment-in-time. To understand that this one moment, one meeting will never repeat again, is a realisation I hold close to my heart. It is a grounding notion as someone who comes and goes from my homeland, finding souvenirs in fleeting moments.

At the spa that evening, my therapist explains that Sen no Rikyu would place toothpicks made from kuromoji trees next to chagashi (tea sweets). Even before the effects of the tree were understood, he recognised that the scent would calm samurai before the meditative tea ceremony. In Aman Tokyo’s signature treatment, oil from the kuromoji is used in both the scrub and massage and the woodsy aroma lingers in the air and clings to my skin. Before we start, the therapist asks me to close my eyes, bring my hands together and breathe in deeply.

I am home.

Floor lanterns dot the dim corridor, casting a warm light. We part the crisp white noren screen, step across a stone path, and enter Musashi by Aman. Eight seats line the hinoki sushi counter, facing the chef against a textured washi paper background. The minimal, bright space is designed using the three foundational elements of Japanese design: wood, stone, paper.

Chef Musashi is awaiting our arrival. He greets us with a simple bow. It is clear that we have entered his house.

The space is immaculate. In a way, how the space is presented is how the chef views hospitality; it is in utmost respect for his guests who come to eat the food made with his two hands. It is my personal passion to enter the domains of shokunin (artisans), to see their artistry and their quirks, strengths and weaknesses. Their entire life’s work, squeezed into one room, four walls… and in this case, one sushi counter.

"How the space is presented is how the chef views hospitality; it is in utmost respect for his guests who come to eat the food made with his two hands."

Martin begins shooting right away, perhaps to compensate for the stillness in the tiny room. Meanwhile, I am revelling in the quietude, soaking in the chef’s stoicism. It is Ryo, the charming beverage manager who breaks the ice, offering us a smile and sake. We try Musashi by Aman Extra Dry, produced from rice fields that Chef Musashi planted and harvested himself with farmers in Yamanashi prefecture. A product of three years’ labour, the sake is served in an Edo-kiriko glass of our choice. The cups are like tiny jewels, holding this precious drink.

In Tokyo, a city of a million sushi chefs, it is the experience that sets one chef apart from the other. Chef Musashi has spent thirty-eight years of his life as a sushi chef delivering classic Edomae-style sushi. His movements are fast, precise, and purposeful. When he prepares kohada, a delicate fish with shiny skin, it is sprinkled with salt from a height of thirty centimeters, a technique called shaku-jio, to evenly distribute the salt on the fish. At times, Chef Musashi smiles briefly and his eyes sparkle brightly. All the while, his hands are working, repeating what he has done hundreds of times before: filleting the tachiuo, scaling and freezing the sakura-masu, skewering the kuruma-ebi.

It is a joy to completely let go and leave the meal in the hands of the master chef. An omakase – I leave it up to you – is the ultimate sign of respect and trust between chef and guest. Expertly prepared, the shimemono, nimono, and yakimono arrive as seven otsumami (small plates) to begin the meal. Chef Musashi surprises me with a modern presentation, a departure from tradition. A bed of light dashi-cooked vegetables is a welcome base to the dishes in a conscious effort to add freshness.

When we move on to the nigiri, I notice his hands immediately. Chef Musashi has large hands with long, slim fingers that produce the most elegant nigiri. Kisu (sillago), kissed by the zest of ao-yuzu, a young yuzu. Mako-karei (marbled flounder), ika (squid) with a thousand tenderising cuts, aji (horse mackerel) with just the right amount of oil, akami (lean tuna), chu-toro (medium fatty tuna).

Each ceramic plate used for serving is also made by Musashi himself. The final uni (sea urchin) arrives on a refined white-and-beige glazed dish. Throughout the meal, if even a grain of rice escapes, it is wiped away immediately. The attention to detail is flawless.

When we next meet Chef Musashi, it is five o’clock in the morning and we are heading to Toyosu Fish Market.

“I usually buy the fish in twenty minutes, then go eat a ramen.”

"Throughout the meal, if even a grain of rice escapes, it is wiped away immediately. The attention to detail is flawless."

That is their daily ritual, but today, it is my first time visiting the market. Chef Musashi makes the rounds with his usual suppliers. There is both a familiar ease and professionalism in their brief interactions. What we witness has been built over years of respect, trust, and loyalty, manifested as genuine human relationships.

Musashi by Aman is a courageous endeavour by an experienced sushi chef. A chef who caters to hotel guests without a common language, accommodating the dietary needs outside Japanese norms that most sushi chefs of his generation have never considered. There is a reason that those around him call him oyakata (boss). This is Musashi, and this is a sushi restaurant. That much is set in stone.

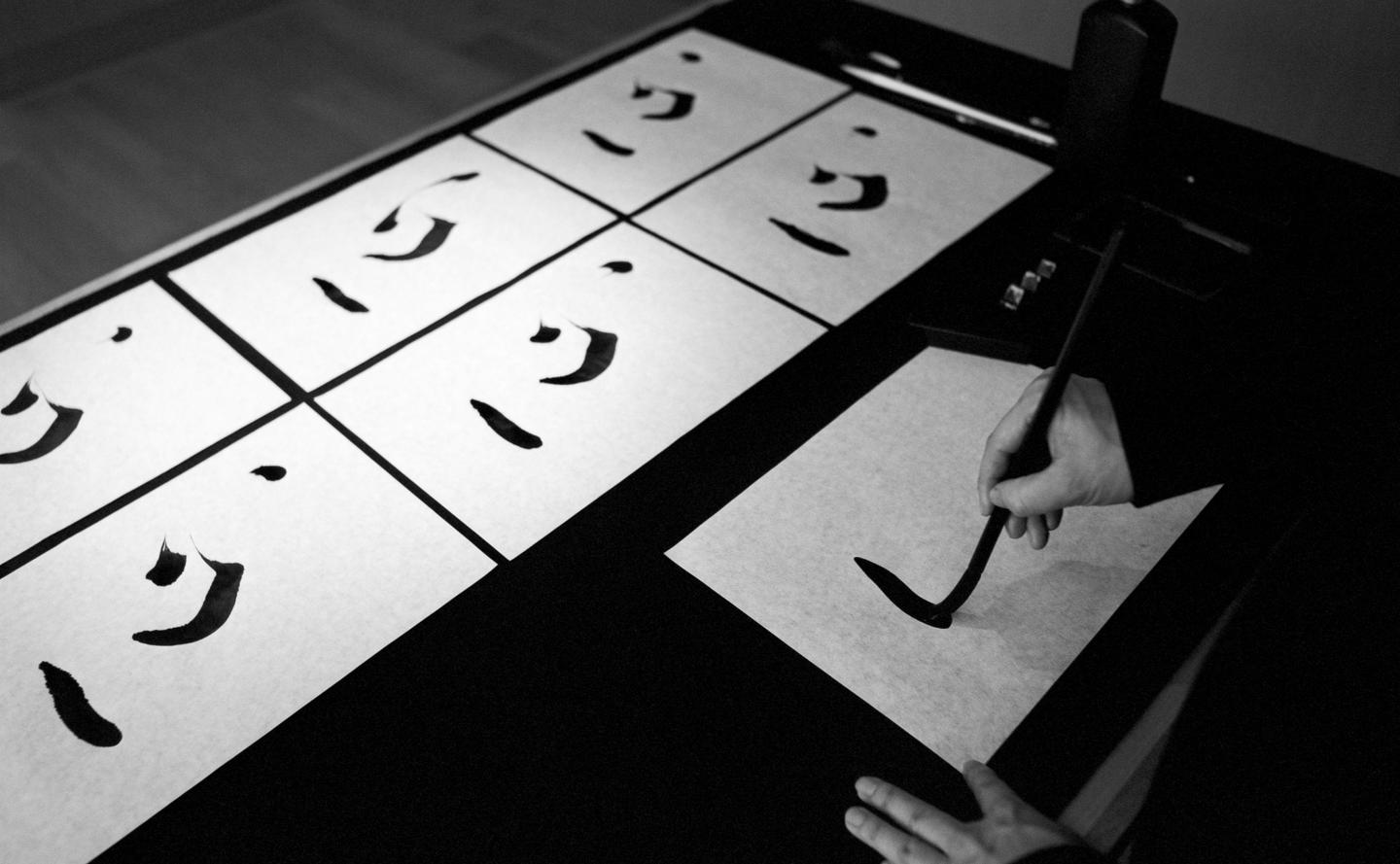

I learned how to breathe when I was ten years old. In front of me was a blank sheet of washi paper, sumi (ink), and a brush. With my legs folded, I was to mind my posture and quiet my mind. Only when my mind was steady would I kneel forward, pick up the brush to dip in the black ink, set my intention, and exhale as I made my first mark. I remember that day, my very first calligraphy class, so vividly. We practiced one thing and one thing only. A horizontal line across the page, the character for number one. I remember it vividly.

“There’s a mental zone that I enter through repetition. I write the same character over and over again and I get this feeling. But if I acknowledge the zone, the zone ends. So it’s the mind knowing that the zone is coming but pretending like the zone doesn’t exist. If I’m in the zone, I’m maintaining my calm, trying not to embrace the zone. Does this make any sense at all?” the artist Gen Miyamura asks rhetorically, laughing gently. We are in a guest suite, standing in front of one of his pieces he completed for the opening of Aman Tokyo, the character “tobu” (to fly). Outside, spring rain falls. There is a quiet, contemplative mood in the room.

Contrary to the disciplined study of shodo (Japanese calligraphy) drawn with a series of angled brushstrokes, Gen-san’s contemporary take is less representational. His body of work created specifically for this site serves as a focal point of each room, bringing together the subtleties of light and shadow, form and abstraction, restraint and play. Today, Gen-san stands at the table covered with a dark underlay. He is writing the character "ikou" (to rest), and "kokoro" (the heart). As he methodically writes these two words over and over again, the characters seem to lift off the paper and float.

On our final morning, as the blind opens to reveal a clear and crisp morning, the eager sun caresses the pale chestnut floors and lights up Miyamura-sensei’s piece on the wall in my room: the deconstructed character “noboru” (to rise). Gen-san has heightened the character’s long, vertical shape; it looks like a long tail of morning mist trailing downwards from the rising sun.

Just then, from beyond the Imperial Palace Park and the skyscrapers and peeking up over the mountain range, Fuji-san greets me in all its glory. I slide through the shoji and disrobe on the warm granite floors of the bathing area. Now, I will observe the ritual of asaburo (morning bathing) before my Japanese breakfast, and a latté, arrives.

Akiko Kurematsu is a writer, journalist, and author currently based in Auckland, New Zealand. Growing up between Japan, U.S., Canada, and the Philippines, she studied at Barnard College, Columbia University and began her career in fashion and design in New York. She is a contributor to Holiday Magazine in Paris, Subsequence Magazine in Tokyo, appears on TV, podcast, radio, and online content including Anthony Bourdain’s "Parts Unknown" for CNN. Her first book, "Mother Tongue” about Japanese family and food, was recognised by NZ Herald as “Books That Changed The Way We Ate in 2023.”

Martin Bruno is a photographer who travels to timeless places, where he takes a path and, through chance encounters, begins a story.

His documentary projects are closely linked to the notion of territory and geographical "portraits". Martin has worked with publishing houses including Keribus, Actes Sud and Rizzoli, as well as with brands such as Hermès.

Featured experience

Until 28 December 2024

Stay in all three of Aman’s Japanese properties, and enjoy complimentary breakfast, guaranteed room upgrades, a 10% saving on all dining and spa experiences, and more. From the lofty urban sanctuary that is Aman Tokyo, to the nature-ensconced, cultural havens of Amanemu and Aman Kyoto, this journey will reveal the multifaceted beauty of Japan.

Developed and made in Japan, Aman Essential Skin’s six streamlined products cleanse, tone and rehydrate even the most sensitive of skins. Ideal for daily use, the collection simplifies the protection of skin, bringing traditional Japanese skincare ingredients to the forefront of modern-day skincare.